Geologic strata are formed by the accumulation of sediment and its hardening under pressure over many years. Generally, the older the strata, the harder and more stable they are. The strata just below the seafloor are often newly deposited sand that has not yet solidified into rock. The strata around the Japanese archipelago are relatively new, and the area is subject to active volcanic and seismic activity, making them all the more complex.

Based on previous geological surveys, the following conclusions can be drawn:

1) Route specifications must be determined as a prerequisite for route selection. Possible vehicles for tunnel operation include automobiles, trains, and linear motor cars, and route specifications vary depending on the situation. 2)

Driving an automobile through an ultra-long tunnel raises concerns about the ergonomic limitations of the driver. Furthermore, linear motor cars have only just entered the testing phase, and it will likely take some time before they are put into practical use.

Therefore, at this stage, we have decided to use the route specifications for the most realistic Shinkansen tunnel.

Specifically,

1) the maximum gradient is 20/1000 (a drop of 20m over 1000m), and

2) the minimum curve radius is 5000m -

this is sufficient to accommodate a road tunnel.

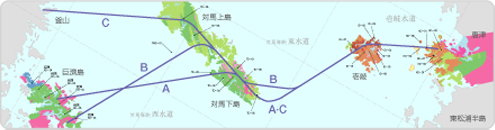

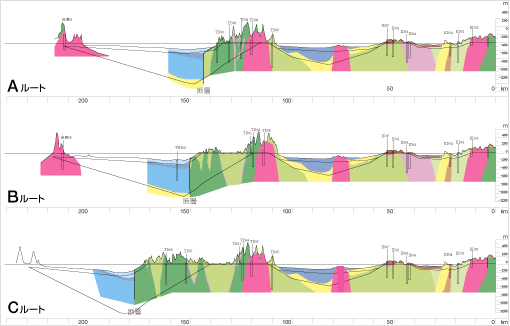

The biggest obstacle in selecting the route for the Japan-Korea Tunnel is the presence of a large fault with a deep drop in the Tsushima Strait West Channel and the presence of unconsolidated new sedimentary layers there. To accommodate this geological formation, two routes are considered.

The first route would run through the bedrock beneath the unconsolidated sedimentary layers. Construction would be relatively safe, but the tunnel would pass through significant depths, resulting in a correspondingly long total length. Construction could be performed using mountain tunneling techniques, incorporating water-stopping injection into the rock mass, as demonstrated in the Seikan Tunnel. The second route would run through unconsolidated layers and utilize the shield tunneling method. In this case, the tunnel would be shallower, resulting in a shorter total length. However, shield tunneling under high water pressure at depths of over 150 meters is unprecedented, and numerous technical challenges remain. In either case,

mountain tunneling techniques, which involve digging through bedrock, are likely feasible for the section from Kyushu to Iki. The problem is how to cross the younger sedimentary layers in the East and West Channels of the Tsushima Strait. Depending on their characteristics, two excavation methods are possible.

Taking the geological conditions described above into account, the tunnel route shown above is currently being proposed. This is a geological map from Kyushu to Geoje Island, South Korea. Route C, which would land directly at Busan, has the drawback of being extremely long. Here, I will focus on the geological overview of the route to Geoje Island. First, the

Kyushu region is home to the Tertiary layer of the Karatsu coalfield, the surface of which is covered by basalt lava, and further intrusive rocks are visible. Magnetic surveys of the Iki Channel revealed numerous igneous intrusions. Iki is composed of the Tertiary Iki Group, also covered by basalt lava. Between

Iki and Tsushima, the East Channel lies a reef called Shichirigasone, and igneous rocks are expected to exist in the surrounding area. The general geology is that of the Katsumoto Group on the Iki side and the Taishu Group on the Tsushima side. However, there is a section of new sedimentary layer between them, so avoiding it would require digging a tunnel quite deep.

Tsushima is mostly made up of the Taishu Group, with a large granite body in the south, the surrounding area of which has undergone hornfelsification. Hornfelsification is the process by which rock is altered by heat. Because granite retains heat, the surrounding strata it comes into contact with are also subjected to heat. Hornfelsized rock is extremely hard. Offshore from

Tsushima's Western Channel, a large fault runs parallel to the coast, and to the west of it, a deep bedrock depression is formed, on which new sedimentary layers are deposited. These new sedimentary layers have been accumulating on the seafloor like falling snow since the Pliocene epoch of the Tertiary period, over 2 million years ago, or even earlier, until the present day. They are still undergoing diagenesis and have not yet fully solidified into rock. Therefore, it is believed to contain a large amount of water and be extremely soft.

Two possible ways to pass through this area are to use a shield tunneling method to dig through the sedimentary layer or to use mountain tunneling methods to excavate the bedrock underneath. The West Channel's deepest point is 150 meters underwater, and a tunnel through bedrock would be 550-600 meters deep. This bedrock is thought to shallow at an elevation of approximately 4 degrees toward Korea.

Based on this general geological overview, the anticipated construction problems can be summarized as follows:

First, in the Kyushu region, granite has weathered into sand-like blocks in some areas, which could easily collapse if groundwater is absorbed. Igneous rocks are distributed on the seabed of the Iki Channel and the East Channel, and there is a possibility of sudden springs occurring there.

Water resources are limited in Iki and Tsushima, and people rely on groundwater for daily life, agriculture, and fishing. Therefore, care must be taken to minimize impacts on groundwater use. Furthermore, how to deal with the unconsolidated new sedimentary layers beneath the seafloor of the Western Channel is arguably the biggest issue affecting the entire tunnel project.

Since the geological surveys conducted to date have been general and qualitative, the next step will require specific, quantitative surveys that are deeply involved in design, budget, and construction method considerations. Therefore, future challenges can be summarized into the following four areas:

1) First, strengthen the understanding of the engineering properties of the geology along the entire route, both onshore and undersea.

2) Identify the hydrogeological conditions in each region to address groundwater issues in the onshore areas of Kyushu, Iki, and Tsushima.

3) Identify and evaluate the geological and engineering properties of the new sedimentary layers in the Eastern and Western Channels.

4) Identify and evaluate the distribution and structure of the seafloor geology and its engineering properties.

While marine acoustic surveys have primarily been used in marine geological surveys to date, this alone is insufficient to understand the physical properties of the geology. Therefore, future plans call for the implementation of marine seismic surveys in addition to these.

Regarding the geology of the land area, stratigraphic comparisons of each area will continue to be carried out in order to clarify the geological structure between Kyushu, Iki, and Tsushima. At the same time, hydrogeological surveys will also continue to be carried out. Furthermore, geotechnical studies corresponding to the construction method will be carried out for both the land and seabed areas.

Organizing the surveying is also a major challenge, and it is necessary to unify the surveying standards and organize the data for the surveying that has been conducted on land and at sea so far. There is also the issue of unifying surveying between Japan and Korea. The leveling datum is located in Nihonbashi, Tokyo in Japan, and Incheon in Korea, so it is necessary to accurately understand the relationship between these two countries. For this reason, it will be necessary to continue to promote exchanges between Japan and Korea in the future.

construction survey of the Japan-Korea tunnel

Overview of the Japan-Korea Tunnel